In Search Of A Wife. A Tale Of The Day.

By Charles H. Ross. Author of "The Dream Of Fate," Etc.

Saturday, Jan. 25, 1862. From Reynolds�s Miscellany Vol. XXVIII., No. 711.

Chapter I.

In Which The Wicked Lord Makes The Acquaintance of the Poor Young Gentleman.

It is in the very height of the London Season, and exactly a quarter to eight in the evening.

The blinds of the dining-room windows at Mr. Christopher Standish�s house in Portman Square have not yet been drawn down, and the gaslight within struggles with the daylight without. The shutters have not yet been closed, nor will there be, until the guests who Mr. Standish expects have all arrived; and thus is Portman Square in particular, and pedestrian London, in general, enabled to obtain a gratuitous and overwhelming notion of the costliness of the Standish dinner-service and magnificent table-ornaments. The sleek butler from next door but one, regarding all this with a calm air of approval, unalloyed by envy, jostles skulking vagabondism, greasy and unwashed, which having planted itself close to the area railings, and grasped the spikes to keep its ground, gazes with dilated eyes, and heavy heart upon the glittering scene within.

This is Mr. Standish�s sixth dinner party this season, and in the fashionable news to-morrow there will be the names of more than one nobleman numbered among the guests.

Thirty years ago he was a clerk in a lawyer�s office in one of the grimiest of grimy streets running out of Chancery Lane - the office of Chivy and McNab - a firm which is well, and not favourably, known in legal circles. Thirty years ago, for ten hours every day of his life, did he sit in that little cell of an office beneath the dusty skylight in front of a heavy pewter inkstand, and upon a rickety stool, which was always on the tilt. Thirty years ago, for fifteen shillings a week, his chirping quill was hard at work all day covering acres of blue foolscap, and stringing together incomprehensible intricacies for the confusion of Chivy and McNab�s connexion.

But this was thirty years ago; and now he is the tenant of a house in Portman Square, and entertains a Russian prince and an English marquis at his table.

Mr. Standish was "something in the City." His exact business occupation was unknown to the majority of his friends and acquaintances; but it was supposed to be one of those unintelligible methods of making money which so amaze the outer world, and by which, in some unexplained way, a dingy office, a clerk, and a brass plate, seem to be all that is required to help to crowd the river with shipping, the City lanes with high-loaded waggons, and the business-man�s pockets with golden guineas.

How is it done? Who can tell? There are a thousand mysteries in this great City of ours yet unravelled.

But we may find out this little secret, reader, before we have done our story. Patience.

It was, then, at a quarter to eight, on a close July evening, half a dozen years ago, that Mr. Christopher Standish stood upon the hearthrug of his drawing-room , scraping his sharp chin with his lank, lean hand, and waiting for his guests.

To beguile the time, he was softly whistling to himself a hymn tune, and he rocked himself to and fro from toe to heel, in time to the slow music. He was one of the meanest-looking of little men, and his suit of spotless, shining black, stiff and glossy, and uncreased, seemed to swamp him. He was rather bald, and very grey ; and although little more than forty-eight years of age, he was commonly supposed to be sixty at the very least. His aristocratic friends attributed his wrinkles to nights of study. It was but natural that the volcanic mind, for ever throwing off wondrous schemes for amassing money, should have had some effect upon the case enclosing it; for were not the wrinkles to be likened to the furrows caused by the path of boiling lava running from the crater�s mouth? He looked a mean man, and a vulgar man, and little signs and tokens of ill-breeding showed themselves every now and then, in spite of his caution and self-control.

"He�s a pitiful little snob," his great friends said, when talking over Mr. Standish�s merits and demerits sometimes, as they rode away from one of his sumptuous entertainments. "There�s no doubt about his being a snob."

"But he�s rich."

"Yes, he�s rich."

"He�s absolutely rolling in wealth."

"He is indeed. He is not only wealthy, but he is the cause of wealth in others."

"Which, by the way, cannot be said of his wit."

"No, he�s not witty, but he�s useful. We shall meet at his table again, I daresay."

"Very probably. I, for one, cannot yet afford to cut him."

Mr. Christopher Standish stood alone upon his heart-rug, pursuing his hymn tune. The minute finger upon the face of the chimney time-piece slowly approached the ten minutes.

"They�re late to-night," he said to himself. "What do they mean by it? They�d better not keep me waiting, or I�ll sit down without them."

This mean little man was growing indignant as the dinner-hour approached. A few moments afterwards, he had become almost furious.

But at the very moment when he was about forming some desperate resolve, a loud double knock came at the street door, accompanied by the clatter of carriage wheels.

Two minutes afterwards the drawing-room door was thrown open, and the servant announced the Marquis of Easthampton.

"How are you, Standish?" the Marquis said, advancing towards him and cordially extending his hand.

The host was holding the watch, which he was consulting at the moment the Marquis entered. Now he slowly replaced it in his pocket, with perhaps a little unnecessary care about its disposal - so contriving it that the Marquis was compelled to wait for a moment with outstretched hand with some degree of awkwardness, until the other responded to the nobleman�s friendly advances.

"I have not kept you waiting I trust?" the marquis continued.

"Waiting? Oh, no ! You�re in good time, my lord, but I thought you were not coming."

"Not coming ?" cried his lordship, again seizing Standish�s hand in his, and squeezing it warmly, - "not coming, my dear friend ? The idea ! Not coming to your house, and when I had promised, Standish? No : that�s unkind - upon my word, that is very unkind of you !"

And his lordship seemed to be quite affected by the circumstance. Mr. Standish, on the contrary, appeared to be highly gratified.

"No, no !" he rejoined; "I knew I could depend upon you. If none of the rest came, I was sure you would. But it vexes a man to be kept waiting for dinner. That�s all. I meant no offense. I�m out of sorts."

"Not ill I trust?"

"Ill? No - nothing serious. I�m never ill. I never had a days illness in my life - at least, I never lay in bed for it. I never shirked work and idled away my time. I never took a holiday, and I�ve never wanted one. I shouldn�t know what to do with one if I had it."

"But, surely, everybody needs some respite from labour, particularly severe mental labour like yours."

"Don�t see it myself. Work is my relaxation. When I�m tired of one sort of work I take to another. That�s how I rest."

"But you do not mean to tell me that you never leave off working, excepting when you are in bed, or on a Sunday?"

"Sunday ! Sundays and week-days are much the same to me. I keep at it my lord. I�m like one of those furnaces which are never allowed to go out. Let me out, and you�d never get me up to the proper heat again."

"You astonish me."

"I astonish myself sometimes, by what I�ve done, when I look back. But it astonishes me more when I look at others, and think what they might have done if they had not been fools, and what I should have done if I had been in their places."

"Then you really mean to say that money-making is your only pleasure?"

"Ay ; why not? Don�t you like it?"

"By Jove ! I only want you to show me the way, and I�ll soon give you my opinion on the subject."

Mr. Standish, however, did not respond to his friends proposal; and the latter, leaning back in an easy chair, remained for sometime silent, with his eyes fixed upon the carpet.

The Marquis was a handsome man, with a truly aristocratic cast of features. He was fifty-five years of age, according to Debrett, and he looked remarkably well, considering the life that he had led. Thirty years ago, when Standish was beginning life, as we have seen, under a skylight, down that grimy turning out of Chancery Lane, my lord was one of the handsomest and most magnificent young bucks to be met with in Bond Street ; and, if the truth must be told, one of the wildest. He was a friend of the "Golden Ball," and of all that clique, but he was too fast for any of them. Why, did not the Marquis of Waterford say that a joke was a joke, but that Easthampton�s jokes were rather more than a joke, and very hard to see the point of? Everybody knows how he staked at ecarte, and lost, at a sitting, that magnificent estate of his at Fatlands, in Shropshire ; and who has not heard the story of his being arrested for debt at the church door in Hanover Square, when he married the celebrated Miss Brass, of the old Olympic Theatre, then under the management of charming Madame Vestris? My lord once pointed out the very spot at the "Wellington," where, when it was Crockford�s, he was going to blow out his brains, after that little loss above alluded to; and would have done so, had not Captain Johnstone, who was there, snatched the pistol from his hand, and flinging it out of window into St. James�s Street, persuaded him, after a little trouble, to accompany him to supper at the house of another noble lord, where they were to meet some of the choicest spirits, and hear Tom Moore sing some of his choicest songs. And so he did go and sup, and didn�t blow his brains out upon that occasion.

But the Marquis now was very poor, and stood sorely in need of a little ready money, and that is why he cultivated the acquaintance of Christopher Standish, of Portman Square.

"Whom do you expect to-night ?" asked Easthampton, presently, breaking the silence.

"Most of them you have met before," replied his companion. "Tram, the railway man; and Sir Benjamin Kidd, one of the directors, that is to be, of the company I spoke to you about. You�ve seen them before I think."

"Yes, I know them."

"Lord Harkaway and the honourable Charley Tares."

"To be sure, I have met them here. Are there no strangers?"

"One, my lord - a foreigner I should like you to make the acquaintance of . The very person for that little matter I spoke to you about."

"Is he rich, then?"

"Rich and titled. He�s a prince in his own country, and it is a country where there�s money, too - Russia."

"Indeed, and what is his name?"

"Devitsky, they call him. He had some capital lying idle, and came to me for my advice. I submitted our plan to his notice."

"Will he join us?"

"Very likely, his name is worth having."

"Certainly, certainly ! And these are all you expect?�

"Yes - no, by the way. There is another I had nearly forgotten."

As he spoke, Standish threw a sidelong look upon the Marquis, underneath his bushy eyebrows, and a malicious smile played about the corners of his mouth.

As he paused, the other looked up.

"Who is he?" the Marquis asked.

"A nice fellow enough. Good family and all that. Has lived all of his life abroad until now."

"How old is he, then?"

"Oh, he�s a mere lad, for that matter. Barely twenty-three I should think. Perhaps younger."

"Where has he lived?"

"In Rome."

"Rome, eh? I should like to sit next to him at dinner, if you can manage it. I know some people there, whom I wish to ask him some questions about."

"Your future son-in-law lives there, does he not?"

"Ye - es," replied the Marquis, with some hesitation.

"Thought so," observed Standish, with a low, cunning chuckle. "Quite right - quite right. You�ll have an opportunity of learning all about the young gentleman. you know the vulgar saying about �buying a pig in a poke?� He ! he! Quite right, and very sly of you."

The Marquis�s face flushed crimson, and he would probably made some rejoinder had not the door at that moment opened, and the entrance of two of the guests interrupted the conversation.

They were Lord Harkaway and the Honourable Charley Tares, two young men of fashion, with slender purses. Harkaway was in the Guards, and Tares had been recently in a Dragoon regiment, but had been tried by court-martial and dismissed from the service, for riotous conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman. He was at present a man about town, but was thinking of going into the Church.

These two gentlemen were quickly followed by Mr. tram and Sir Benjamin Kidd; and scarcely had they arrived, when a loud, thundering double knock announced the advent of his Highness the Prince Devitsky.

The guests seemed determined to make up for lost time. They had all arrived, with one exception - that of Mr. Basil Craven, the young gentleman next to whom the Marquis of Easthampton had desired to be placed at the dinner table.

The mantle-piece clock now marked five minutes past eight. The servant had announced that dinner was served.

"Are we waiting for any one, Standish?" Sir Joshua Sloper inquired.

"Yes," the host replied with an impatient gesture; "but we will wait no longer." And the party proceeded down to the dinner room.

"Who is the delinquent?" asked Lord Harkaway, stroking his moustache.

"A young friend of mine - Mr. Basil Craven."

"Any relation to the cravens in Wiltshire?�

"I think not."

"There was a man of that name in the 46th," drawled the Honourable Charley Tares. "Shocking cad, by the way, and used to eat fish with his knife. Yes, he did, by Jove !"

The young gentleman evidently thought it a most humorous anecdote, and one worthy of repetition, for he retailed it again to Mr. Tram, who he thought might not have heard it; and the railway man, happy to have an opportunity of conciliating the youthful patrician, laughed a hoarse laugh, and said, "You don�t say so, sir ! What a savage !"

But evidently the Prince Devitsky did not appreciate the story; he coloured up to the roots of his closely-cropped hair, and his large ears grew positively crimson; for at the moment that the other spoke, he was using his own knife as a spoon, and half swallowing it at every mouthful.

The Marquis, who had been eying him narrowly, smiled sarcastically at Harkaway, who marked his recognition of the incident by a slight elevation of his eyebrows.

Just then Mr. Basil Craven was announced.

He was a tall and strikingly handsome young man, with an air of ease and composure, without any over assurance or apparent striving after effect, which in so young a man - for he could have been little over twenty-two - was very unusual. His manners, too, were extremely agreeable, and his conversation fascinating; and before he had been seated many minutes, he had by a few graceful phrases, entirely dissipated the slight air of constraint which his entrance had thrown upon the company.

The dinner proceeded slowly,. It was solemn and grand.

The solemn footmen glided about behind the chairs like ghosts in livery, noiselessly removed plates, gathered up knives and forks without a jingle, filled wine-glasses without a chink, and cracked phantom jokes in the faintest under-tone at the side table.

The gold and silver upon the rich man�s board were quite a show. The dishes were faultlessly cooked and served- the wine costly and old. The whole entertainment was heavily impressive, and the guests could not fail to be imbued with a crushing sense of Christopher Standish�s wealth, and savagely envious of his good fortune.

Meanwhile, the Marquis had been carrying on an animated and deeply interesting conversation with his next-door neighbour.

"Standish tells me that you have been to Rome," the Marquis said.

"Yes, I have lived their for some years."

"You must, then, know everybody?"

"Not quite."

"I mean, of course, everybody in society?"

"To be sure."

"Do you know Albany - young Lord Albany?"

Basil craven, who, since the conversation had taken the direction of Rome, had suddenly become less communicative, replied briefly that he had met his lordship once or twice.

"Indeed!" pursued the Marquis, with a great show of interest. "Is he a friend of yours?"

"No."

"A very agreeable young man, though, I believe. Extremely amiable - prudent - well-behaved?"

Craven laughed.

"Is it not so?" the Marquis asked, looking at him anxiously.

"I know so little about him, my lord," the other replied with hesitation. "I have only heard - that is - there are rumours -"

"Rumours! Good gracious ! what rumours? Has he not just succeeded to one of the richest properties in England? Does he not bear one of the proudest titles?"

"You must excuse me, my lord, if I decline to repeat any scandal which may be current in Rome to his discredit, but which, after all, may be totally untrue."

"Certainly - certainly !" said the Marquis, affecting to laugh, and changing his tactics. "Young men will be young men. you are quite right not to tell tales out of school; besides, not to me, you know, above all."

"Why not to you, my lord?"

"Why, you know very well that Albany is going to marry my daughter, the Lady Laura Keith?"

"To be sure," Basil Craven replied, blushing faintly. "I beg a hundred pardons for what I have already said. I remember now that I had heard the report."

"Well, well. there is no harm done, sir. If you and Albany are not chums, that will not, I hope, prevent you from being my friend. May I hope to see you down at Wasteacres? I am going there for a week ; - will you come with me? I start to-morrow. what do you say ?"

The young man bowed and smiled, but seemed to hesitate.

"Come, come ! - if you have no other engagement. There ! It�s settled. Come and dine with me to-morrow night at White�s club; and we will go down by the ten o�clock express."

Before the young man had time to offer his thanks for the marquis�s kindness, the company had risen from the table, and were leaving the room to go up-stairs for coffee.

The Marquis had for some time had no other opportunity of speaking to his young friend; for he (the Marquis) was shortly engaged in an earnest conversation with the Russian Prince upon affairs financial.

The chief object for which Standish had given the dinner was to introduce the Marquis to his highness, and the former, with ready tact, soon ingratiated himself with the foreigner.

He was a curious sort of man, this Prince; vulgar, and ill-bred, undoubtedly, as we have seen in that little incident of the knife - at least, according to English notions; but then, the Marquis argued with himself, these Russians are so strange, so noisy, so demonstrative, so uncouth.

Perhaps, after all, these little offenses against etiquette might not be so many proofs of his want of breeding.

At any rate, he had mixed with the best society abroad; and here, in our own more exclusive land, he had been presented at Court by no less a personage than the Duke of Middlesex.

His Highness was not, according to our English notions, an aristocratic-looking man; for he was enormously fat, and his great cheeks hanging down on either side gave him something of the appearance of a prize pig ; but he was by no means a heavy, sleepy person as you might have supposed, : on the contrary, he was remarkably voluble and fluent in conversation, talking French and German, and Italian and English, with equal ease; and he was apparently well-informed upon almost every topic of interest that was broached during the dinner.

Now he was talking about money ; and gradually nearly all the guests present became mixed up in the conversation. The new company which Standish proposed to organize came upon the tapis; and plans and prospectuses innumerable were discussed.

Only one person present seemed to be uninterested in the subjects engrossing the rest.

This was Basil Craven.

He, on the contrary, lounged carelessly about the room, examining the pictures and articles of vertu , and occasionally yawning as though he were profoundly fatigued.

"Our young friend does not join us," the Marquis whispered to Standish, pointing to Craven.

"No," the other replied; "he is useless for our purpose, he is as poor as a church-mouse."

"Oh, indeed !" the Marquis remarked, with an almost imperceptible grimace.

"You�ve asked him to visit you, I believe?" said Standish.

"Yes, I have. I had a motive."

"He�s of good family, you know, if he has no money, and he�s a bachelor," the host said, with a snigger.

"I do not understand you, sir," replied the Marquis, haughtily, as he turned upon his heel.

"I like these proud paupers !" the little man said, with a leer. "i like to watch their poor little paltry tricks, and the trouble they take to hide them. as if I did not know that the great object of Easthampton�s life is to get his two daughters off his hands, and make something out of their husbands ! Bah ! These aristocrats are much the same as us common people, after all ! Ours is the retail trade, and theirs the wholesale !"

But, however true Mr. Standish remarks might have been when otherwise applied, in this instance they appeared to be entirely wrong ; for the Marquis was even more polite to his young friend than he had been previous to hearing of Basil Craven�s poverty.

"Are you going away?" the Marquis asked. "It is very tiresome here to-night - don�t you think so?"

"Yes ; and it is getting late."

"My cab is at the door," said the elder man ; "I am going to Covent Garden. can I set you down anywhere?"

Mr. Basil Craven said that, curiously enough, Covent Garden was his destination ; and they consequently departed together. The Marquis had previously invited the Russian Prince to come and see him at his country house in the course of the next few days ; an invitation which the Prince had graciously accepted.

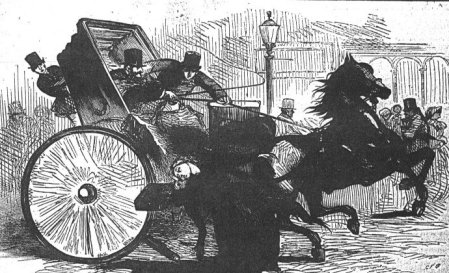

The Marquis handsome cabriolet , high-stepping chestnut , and diminutive tiger, were waiting for them ; and they mounted together, and drove off towards the east.

There was a little crowd round the door of Standish�s house as they came out ; and it was with some difficulty they made their way through to the carriage.

A poor-looking, thinly-clad old woman, apparently in a highly excited state, was disputing with one of the commanding creatures in plush (alias footmen), who seemed to be refusing her admittance.

"But this is his house," she said - "I�m sure it�s his house."

"I didn�t say it wasn�t ma�am," retorted Plush ; "but you can�t see him - that�s what I say."

"Can�t - can�t ! Oh, listen to him ! That ever I should live to see a day like this ! Can�t see him ! Oh, dear ! oh, dear ! And me that�s dragged my poor old aching bones these sixty miles to do so, and then to be drove away from the doorstep like a dog. It will break my heart, it will - it will !"

"There, my good woman," interrupted Plush, indignantly; "we don�t want to hear nothing about your bones. you�d better take my advice, and take yourself off; that�s the best thing for you to do !"

But the old woman turned upon him fiercely, clenching her bony fist and shaking it in the footman�s face, who fell back in alarm, and threw himself into an attitude of defence, to the infinite delight of the small boys collected around the scene of the action.

"Don�t insult me, fellow !" the old woman cried, passionately. "Don�t provoke me, or I�ll fly upon you like a cat, and tear your coward�s heart out of your bedizened body !"

And she made as though she would have clawed his face had he not sought refuge behind a brother flunkey.

"Perlice !" he shouted - and, an officer opportunely making his appearance, poor Plush, though very pale and greatly agitated, told his story, and begged that the cause of the disturbance might be removed.

She was either mad or drunk, Plush supposed. She had been insisting upon seeing Mr. Standish, and had been talking a pack of rubbish no one could understand. She had nursed him when a baby, she said, and she had lost him and sought him in vain for years. It was decided by the policeman that she was very mad indeed, unless she had been indulging in intoxicating liquors ; and she was strongly recommended to move on into the next parish, unless she was desirous of a night�s lodging in the nearest police-cell.

And so she moved on and away ; and the remainder of the guests presently departing, the host saw the plate and all that was valuable safely stowed away and locked up, and then watched the four ghostly footmen off the premises, having a vigilant and searching eye for their bundles and coat-tail pockets.

After this the shutters were all closed and fastened, and the doors carefully locked and bolted ; and a sturdy man making his appearance from the lower story, let his master out, and shut and locked the door upon him.

The master , then, did not sleep at the house?

No, The sturdy man and a canine companion were left in charge ; and the master, or as much as remained of him - for having taken off that wonderful suit of creaseless black which had appeared to swamp him, he was now a meaner man than ever - left the house, dark, and silent, and ghostly ; and with a backward glance of dread thrown over his shoulder, he stole away into the deserted streets, bent upon what errand only time alone can show.

But when he had gone, yet were the house and its valuable contents not left solely to the care of the man within and his dog.

An old woman, very careworn and thinly clad, approached timidly and with great caution, fearful lest she might be observed ; and taking up her station opposite the house, but in a spot where she was hidden in the shadow, she spent long hours watching the darkened windows of the Standish mansion, and softly sobbing to herself.

End of Chapter I.